In 2005, I spent some time talking with Michael Madsen about the man who made him want to become an actor in the first place, the eternal outsider ROBERT MITCHUM, and asked him to run through some of his favourite Mitchum movies.

Toronto, Canada. It’s the summer of 1984, and 25-year old car-mechanic Michael Madsen arrives on the set of The Hearst and Davies Affair, a movie about the relationship between newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst and 18-year-old chorus girl Marion Davies, in which Madsen’s kid sister, Virginia, is playing Davies.

Madsen is uncharacteristically nervous. He’s been trying to break into acting, but although he’s had a few parts as an extra, a movie career seems a long way off. He has no part in this film, and no business on this set, but he’s made the pilgrimage from LA because Virginia has promised an introduction to her 67-year-old co-star: Robert Mitchum.

Veteran of over 100 movies since his 1943 debut as a bad guy in B-westerns, Mitchum’s presence is undiminished, his legend set in stone. A chain-gang convict by 16, he first arrived in Hollywood on a freight train he’d jumped with other hoboes. During the 1940s and 50s, when he shrugged off a drugs bust, recorded rock ‘n’ roll records and notched up countless boozy brawls, he was practically a one-man counter-culture.

The offscreen escapades, combined with Mitchum’s habit of constantly disparaging acting as a “ridiculous and humiliating profession”, often served to obscure his phenomenal talent. But to a passionate cult of fans, there’s no question. After directing Mitchum in Night of the Hunter, Charles Laughton announced “he’d make the best Macbeth of any actor living.” John Huston called him “an actor the calibre of Olivier, Burton and Brando – capable of playing King Lear.” David Lean, who cast him in Ryan’s Daughter, perhaps said it best: “Other actors act. Mitchum is.”

It was seeing Mitchum in Huston’s Heaven Knows, Mr Allison on TV as a teenager that first made Madsen think acting might be a job worth doing. He’s since watched every Mitchum movie he can. But he’s also fully aware of his hero’s infamous reputation for fending off questioners with a gruff, monosyllabic facade.

In the event, however, Mitchum proves unexpectedly charming, inviting Madsen to breakfast. “And I’ll never forget that meeting,” Madsen says mistily. “I’ve become sort of his ne’er do well comparison – I’ve been lucky enough to be sometimes labelled a kind of heir to Mitchum. But I’m just honoured to speak about anything to do with him.”

MEETING MITCHUM

DL: So he was the actor you admired maybe more than any other, and you got the chance to meet him…

MICHAEL MADSEN: Yeah, we had breakfast. Waffles and strawberries. And there I was with him. He said, “So, son, what’re you gonna do with yourself?” I was pumping gas, workin’ on cars, I hadn’t really got anything going. I said, “Well, y’know, I was thinking about becoming an actor.” And he said, “Why would you want to do that?” Which always struck me as pretty funny. He said, “Well, son, lemme say this. If you wanna become an actor, you better learn how to drink Smirnoff.” I didn’t even know what Smirnoff was, so I asked. “Vodka, son, vodka.” Then he said, “And about the working-out business, lifting weights and such.” I said, “Oh, yeah, well, I’ll start exercising.” And he goes, “No, no – don’t bother with that. Get a padded coat. Padded coats, son. That’s all you need.” He was something else. But, while we joke about it, and he always joked about it, there’s a certain genuine feeling in his acting, something basic, something to do with complete honesty. An approach that’s based in something that’s not phony. That gets right to the point of Mitchum, who he was, what he represented – and why you and I are having this conversation right now.

MADSEN’S MITCHUM MOVIES

THE STORY OF GI JOE (1945)

William Wellman’s grim WWII drama follows a US Infantry brigade from North Africa to Italy. Mitchum was Oscar-nominated for the only time as the outfit’s fated Lieutenant

MADSEN: I have to start with GI Joe. Because he got nominated. It was really the beginning for him. I’ve always wondered what he might’ve done had he been more appreciated with nominations. Not that he cared, but I think he may have embraced what he did for a living more. Instead, he got comfortable with feeling that it was okay to make a mockery out of what he did. And that’s a loss. His performance is so honest – it’s kind of naive, but he just had such a command of the screen. You felt like you knew him: he represented The American Soldier in exactly the way they were looked upon at that time. He had pathos, a vulnerability beneath this very strong exterior. He’s so still.

DL: Yeah. Mitchum had been in movies less than two years at this point, but this was already his 27th film. Something I’ve found, looking back on his early roles – even those little Hopalong Cassiday westerns – when you see him in those first movies, he’s already recognisably Mitchum. A lot of other actors, you see them becoming who they were. But with him, it’s kind of already all there.

MADSEN: Well, it’s called screen presence. It’s what Steve McQueen had. When you look at someone like that on film, no matter who they’re standing next to, they don’t even have to be saying anything or doing anything, but your focus automatically goes to that person. It’s an indescribable, strange thing, and I think you’re either born with it, or not. It’s like when someone walks into a room, and the room belongs to them. I think I know what you mean about his early stuff on film. When you see his mug, he automatically owns the scene, without saying anything.

OUT OF THE PAST (1947)

The quintessential film noir. Mitchum is an ex-Private Eye hiding in a small town, who gets sucked back into his dubious past when his hiding place is discovered by Kirk Douglas, the mobster he once wronged

MADSEN: Kirk Douglas is also an actor I enjoy. Lonely Are the Brave is one of the best I think he ever made. One interesting thing about Out of the Past is they’re both so young – and Bob pretty much beats Kirk up. He blows him off the screen. Part of it’s because Kirk’s playing kind of a chump, and Bob has the cool guy. But, earlier we were talking about watching guys when they were starting out, and this is a good time to look at Kirk, because he was just starting to figure out who the hell he was. If you look at them together, it’s pretty funny, because Bob’s so basic, yeah, he’s already all-there. He’s like, “Hey, okay, I’m standin’ here, what the fuck.” And Kirk’s so intense, like, “HEY! I”M OVER HERE!!” I WANT TO MAKE A STATEMENT GODDAMMIT !!! And Bob’s, “Okay, I dunno what you’re so excited about.” He’s got it completely figured out: when you’ve got that kind of energy coming at you, the perfect way to counterbalance it is to just underplay it, and that’s exactly what Mitchum does. And his character’s like that. The guy just accepts what he’s got coming, and he goes there with it: “Okay, this is what I gotta do, this is my fate, I brought myself here, okay, that’s it.”

NIGHT OF THE HUNTER (1955)

Charles Laughton’s only movie as director casts Mitchum as a psychotic preacher pursuing two orphans through Depression-era America. A unique film, it’s a stylised fairy-tale, and Mitchum, L-O-V-E and H-A-T-E tattooed across the knuckles of his hands, produces a highly stylised performance, unlike anything else in his career.

MADSEN: What a great film. What a gem. Mitchum always spoke very highly of Laughton, and deservedly so. Isn’t it a tragedy that Laughton didn’t direct more films? But there it is, right there, on its own, Mitchum and Laughton and Night of the Hunter. Yeah, it’s very much a fairy tale. Those night scenes, when Mitchum’s just this silhouette, riding that horse, it’s like a picturebook. Like The Legend of Sleepy Hollow: a fairy tale, but with an utter grimness to it. If you’ve ever heard the yell he lets out here, when he’s chasing the kids and they’re in the boat, and the boat is just getting away from him as he’s wading into the water: “….wwaaWWWWWAAARRRRGHHH!!!!”, this crazy yell. An animal thing. It’s a sound I never heard from him anywhere else. That’s the thing about Mitchum, he was never showy. He didn’t need to be. But, then again, there are a few moments like this, a few things that he lets come out, that he had access to, that are really surprising. You just have to stand back and go, Wow.

HEAVEN KNOWS, MR ALLISON (1957)

More like an Eden-tale than a WWII movie, John Huston’s remarkable film is almost an update of his own African Queen: Mitchum’s a shipwrecked US Marine who washes ashore on a deserted island in the South Pacific. The only other inhabitant is a beautiful nun, Deborah Kerr – then the Japanese forces return.

MADSEN: Seeing that film made a big difference to me. It was the first time Mitchum made an impression on me, the first time I ever got the notion that I might think about being an actor. I understood the mechanism of what Mitchum was doing and the character, but, watching him, I suddenly realised that acting could also be a presentation of one’s own personality. He’s a Marine, shipwrecked alone, floating in the sea at the start, and he washes up on this island that used to be occupied by the Japanese. And Deborah Kerr is a nun, from a mission on the island. And he has to keep her safe, in a cave, when the Japanese forces re-occupy the island. Because she’s a woman – she’s a nun, but she’s also a woman – he really wants to break through all those vows and be with her as a man. It’s just a very interesting performance, It’s very measured. I think, Huston, being the genius he was, may have gotten the best performance of Mitchum’s entire career. He got the macho, male, mano-mano of the man, but he also got the heart and soul, tenderness and sweetness. Y’know, when he’s sitting singing to her, “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree,” and he carves the comb for her out of wood, when she has her fever, and he has to take her frock off when she has her fever. You know when she wakes up, and there’s that moment when she realises that she’s been undressed – Deborah Kerr was nominated for an Academy Award for that picture, and I think that it may have been for that moment, when she wakes up and realises that her clothes have been taken off. There’s maybe three seconds of emotion she expresses, where she’s like…Oh My God. Then at the same moment she knows that all he did was save her by getting the wet clothes off. You see it in her face. And then you look at him and he’s got that smug expression on his face. Most of the film, it’s just these two people onscreen. But he carried it. That says a lot for the power of his presence.

HOME FROM THE HILL (1960)

A great, sweltering, sticky Southern soap, directed by Vincente Minnelli. Mitchum plays a monstrous Boss Hogg patriarch with a distant wife, Eleanor Parker. Their effeminate son, George Hamilton, is a local joke and Mitchum determines to make a man of him, aided by his right-hand man, George Peppard. It’s like Dallas rewritten by Faulkner.

MADSEN: Dallas by Faulkner? Wow. That’s a good definition, man. Never heard anybody say that before. You nailed it. Home from the Hill is really wild. I mean, George Hamilton as Mitchum’s son? Mitchum’s this big macho hunter, such a strange performance. Minnelli directs it and it’s almost campy, but Mitchum has this one scene where he’s arguing with his wife – she won’t sleep with him anymore – and she confronts him that she’s found out that George Peppard is his illegitimate son. And Mitchum goes into this speech about “The Mother” – and, wow, it really just blasts out of nowhere, this paragraph. You find yourself leaning forward, watching the film suddenly, thinking, Ho-lee-shit. He used to do that when you’d least expect it, craft this fiery moment in the middle of an almost-bad B-movie. He’s a complete son-of-a-bitch in this, but you love him. When, finally, he’s shot, and he’s lying dying shouting “Rafe!” – which is Peppard’s character, he wants to speak to his bastard son – all of a sudden he’s redeemed. It’s beautiful. You think he’s just this brute animal, but, really, he has a giant heart.

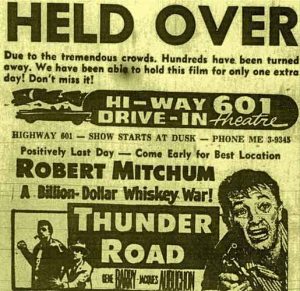

THUNDER ROAD (1958)

A blast of pure pulp – but also Mitchum’s most personal movie: he wrote the story, produced, and cast his son, Jim, as his kid brother. Mitchum plays a doomed, loner moonshine runner in a souped-up hot-rod, fleeing mobsters and government men out on the backroads of Kentucky. He later had a hit single with his rockabilly recording of the self-penned title tune.

MADSEN: Thunder Road, man. Thunder Fuckin’ Road, man. C’mon, goddam! When that fuckin’ Chevy flips over into that electrical box? Oh, man. You really feel bad. You just didn’t want that to happen. You didn’t wanna see him go out that way. That one sticks with me forever. I got a huge Thunder Road poster in my home. What can I say? Yeah, I think it was a personal thing for him. His son’s in that movie. I think Mitchum liked the subject matter. I think he just liked the idea of it, and knew that he could flourish in that character, he could portray that kind of guy, and I think that he might have been one of the first actors to realise that getting involved as a producer, getting involved in the back end of things, was the road to financial rediscovery; to not be a hired gun, to be able to be part of the whole creative process. But, basically, I think he just liked the story. I get scripts all the time, people are trying to capitalise on me – because I played a certain kind of killer, I get stuff that’s very predictable, and I don’t wanna do a lot of that stuff, I say no to a lot of it, because I have a different idea about the kind of stuff I wanna do and I wanna make, and I think at that time in his life, Bob probably figured, okay, yeah, I can play this guy, this is a good story. And, of course, he did the music. You heard his album? I’m getting ready to do one of those myself. Yeah, David Carradine has a recording studio, and I’m gonna go sing some ballads, quiet, kind of Johnny Cash stuff. That’s the only stuff I can sing. Hey, I’m not Neil Diamond.

CAPE FEAR (1961)

The nerve-shredding original makes Scorsese’s remake (in which Mitchum also makes a cameo) look like a Popeye cartoon. Mitchum plays Max Cady, the bad-to-the-bone ex-con seeking to destroy the family of Gregory Peck, the lawyer who put him away. A hip, laid-back monster his performance is one long solo of pure evil.

MADSEN: Compare Mitchum’s performance in Cape Fear to Robert De Niro’s in the remake, and I would have to say that Mitchum’s is a lot more credible, a lot more scary, and a lot more interesting. I mean, Mitchum didn’t really have to try too hard to be scary. He didn’t have to go overboard. He was subtle, and within the subtleness was a threat. He knew how to work that. It was almost like, y’know, they said, “We want you to play this guy. And this guy’s pretty dark, right? He’s really bad.” And it’s like Mitchum was thinking, “Oh. Okay. You wanna see a bad guy? Okay. Watch this. Here‘s what it is. I’ll show you what you think you want. I’m gonna show you what you wrote.” He surpassed the writer, he took it beyond what it was supposed to be. He just blows De Niro’s performance off the screen. It’s just amazing. And, then you look at the difference between the Mitchum of Cape Fear and the Mitchum of Ryan’s Daughter, where he’s this shy schoolteacher – I mean, wow. That’s a pretty big range. People still don’t get that. They don’t realise just how wide a range Bob had.

DL: As a last aside here, when I watch him in Cape Fear, I always think about how Mitchum travelled a lot, alone, from a very young age, years and years before he ever thought of acting. He’d hoboed around, and he’d been arrested and done some time, he’d worked in factories, and, y’know, I think he’d seen some bad guys along the way. He knew what it was. What these guys were like.

MADSEN: I can understand that. I worked a lot of odd jobs in my life. I was pumping gas when I was 15 years old, doing tune ups on cars, towing cars, cutting grass, painting houses, worked as an apprentice to a plumber. My father was a fire-fighter, and he wanted me to be a fireman. I banged around quite a bit, and I saw quite a lot of things, and I think that Bob, obviously, had seen things in life, and knew certain things about what it is to be broke, what it is to be lonely, what it is to be left destitute or without resolve. And I think that that can form a man, can form a personality, and then, because of his looks, it led him into a film career. I can tell by talking to you, that you know as much, or more, about Bob than most people I’ve ever talked to, and I really respect that. And I’m glad that you would contact me to do this. It’s nice that you have the knowledge that you have, because it’s rare. We could go on all day here. What was the name of that picture he did with Shirley Maclaine? About a woman who got married a whole bunch of times, and he was one the husbands.

DL: What A Way To Go?

MADSEN: What A Way To Go, yeah. He was a rancher. And he gets booted out of the corral by a bull. He gets kicked over the fence by a bull, because he’s been trying to milk a male, he thinks it’s a cow and it’s a steer and it kills him! That was a very funny performance. And I like that one he did with Cary Grant, and Deborah Kerr again.

DL: Oh, yeah, The Grass Is Greener

MADSEN: Yeah. What I like about that, what’s interesting, is, here’s Mitchum, this rough and tough, gruff guy – and who are you gonna be opposite? Cary Grant. Car-ee Grahnt. Like, y’know, handsome, sophisticated, gentleman. You put Mitchum opposite him. That to me was almost like when Marlon Brando did Guys and Dolls: there’s Marlon with Frank Sinatra, singing and dancing with Frank. And then you put Bob next to Cary Grant, but he showed something interesting there, he had this ability – it was almost like when Steve McQueen did The Thomas Crown Affair, you take this guy who was a roughneck, and put him in nice clothes, with money, and what do you get – well you get something pretty good, there’s something pretty interesting going on there. And how hard it must have been for him hanging around with Cary Grant. I mean, can you imagine those two sitting around the table..?

THE LEGACY

Robert Mitchum died in 1997, aged 79. His last movie released before his death was Jim Jarmusch’s masterly Dead Man. Once again cast as a bad man in a black and white western, it saw Mitchum going out exactly the way he’d come in, over half a century earlier.

MADSEN: His legacy? I think Mitchum left an idea. Like you said, Bob had moved around a lot during the Depression, worked a hell of a lot of jobs before he ever came to Hollywood. He’d seen things in life. He gave acting some dignity by making it honest. I think he’ll be forever respected for that. He didn’t embrace acting, but at the same time he gave it a new identity. He had a very keen sense of humour, but also a tragic cynicism, and he realised that what he did was a bit of a dog and pony show. He was once asked about being a star, and he said, “Well, how hard can it be? Rin Tin Tin was a star, and that was a bitch dog.” I have a deep understanding of that, because I never really had any training as an actor. I always kind of went at it. I spent a brief time in the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago before I set out to do it, but I understood what he meant. You can’t really put a title on what he left. I’d like to see his influence out there today, but, unfortunately, I couldn’t tell you anybody that I can see doing it. I think that in Hollywood there’s been an effort made since guys like Mitchum to homogenise the male personality in the presentation of characters, to a place that now more resembles the personality of the studio heads, and not…the guys who got the girls in highschool. Does that make any sense? Having said that, I’ll probably never work again. But thanks for letting me talk about this. Thanks for keeping those things in your head. We need to pass them on to everybody in our lives. We need to remember Robert Mitchum.