In late 2022, I spoke with Stephen Morris and Peter Hook about the Definitive Edition box set of New Order’s majestic Low-life album of 1985. A small part of the interview ran in Uncut magazine, along with my review of the box. I’m publishing the full interview here for the first time.

It is May 14 1984, and as the UK Margaret Thatcher would like to see remoulded in her image tears itself apart, New Order are doing their bit on the angels’ side, playing a benefit at London’s Royal Festival Hall in support of the nation’s striking miners. As the climax, they unveil a song no one has ever heard before, one they’re still writing there on stage, jamming with their sequencers. In time, this track will grow exponentially, to become the launchpad for the next chapter of their eternally unlikely career; a track that exploits and expands the possibilities of the 12-inch single even more than “Blue Monday”; a track so endlessly, ever-changingly glorious you could live inside it, or at least lose a lifetime’s worth of weekends there. And its name is…and its name is…and its name is…

“This one’s a new song,” Bernard Sumner says, as he steps to the mic. “It’s called ‘I’ve Got A Cock Like The M1.’”

As ever with New Order at their finest, the sublime and the ridiculous, heaven and earth, danced in close proximity at the messy birth of the song we would eventually come to know as “The Perfect Kiss,” signature track and – controversially, in those indier-than-thou days – lead single of their magnificent third LP, Low-life.

Now getting the augmented deluxe treatment as the group’s exemplary series of “definitive” box sets continues, it is clearer than ever that this shimmering, shadowy, silvery-grey and grimy album, released in spring 1985, marked the commencement of their imperial phase. If 1983’s miraculous Power, Corruption And Lies was the moment New Order put it all together – all that pre-punk and punk and post-punk and kling-klang electro and ambience and rage and sadness and joy and confused, knowing naivete – Low-life was where they set out to see how far they could take it.

In the time between the two albums, the group’s individual members had been stretching their studio technique, taking on a wild variety of producing jobs for other Factory Records acts, testing gear and ideas while searching for the perfect beat on other people’s records. They brought it all back home on Low-life. Recorded in the dark, dying winter months of 1984, it is a record where individual influences are readily apparent, yet get set spinning in that perfect balance that becomes something else altogether.

Musically, inspirations include both the new club sounds New Order kept chasing, and the beloved old soundtrack LPs they cherished: “Perfect Kiss” itself starts as an attempt to replicate Shannon’s “Let The Music Play,” then becomes a joyride through a gleaming, crime-infested Metropolis and out into the misty radioactive swamplands beyond, full of mutant funk frogs and laughing sheep. Conversely, “Face Up” begins like an ominous Blade Runner city fanfare, then gets hijacked by a sprightly HINRG gang with “Temptation” tattooed across their knuckles.

The most persistent influence is Italian maestro Ennio Morricone, the album’s deity, whose revolutionary scores for Sergio Leone infect half of the eight tracks, most obviously New Order’s own unapologetic spaghetti western showdown, “Elegia.” (The semi-legendary 17-minute original cut, created in one relentless, well-fuelled 24-hour session because they’d been given free studio time, is among the extras, replete with admirably absurd cameos from the engineer’s passing nephews, stating their names for no reason.)

The most unexpected influence, however, is the band New Order were, as “Sunrise” – a raging argument with God, and another touched by the hand of Morricone –becomes the closest thing to a Joy Division song they’ve ever done. Perhaps, by this stage, they felt confident enough that they’d chased the last of the wrong sort of JD fans away to let that holy ghost back out; although they throw in another of Sumner’s most entirely-not-Ian-Curtis lyrics into “Face Up” just to make sure: “Your hair was long, your eyes was blue, guess what I’m going to do to you…whoo!”

As outlined by writer Jude Rogers in the book accompanying the set, other, external, forces also shaped Low-life. For one, the general pre-Orwellian feeling in the air as 1984 dragged to a toxic close. For another, the atmosphere of pressure being released in the underground London clubs where New Order spent their nights during recording, notably infamous leather-and-rubber fetish joint Skin Two: “This Time Of Night”, “Perfect Kiss” and the album’s second single “Subculture” all soundtrack fascinated night-trawls through a decadent demimonde.

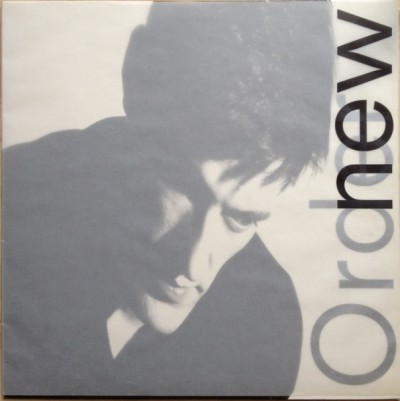

Simultaneously, the genuine effort underway to break the band overground in America, via their entirely implausible deal with Quincy Jones’s boutique, Warners-offshoot label Qwest (whose other big signing that year was Frank Sinatra), fed the decision to do such decidedly un-New Ordery things as include singles on the album, and feature their photographs on the sleeve. It is difficult now to convey the sheer sense of heresy this unleashed among the most heavily overcoated sections of the John Peel nation in 1985, yet it resulted in the most flawlessly New Order-y solutions.

Clad in its fragile second skin of translucent tracing paper, Peter Saville’s cover was his most beautiful object yet, framing his portraits of the group, shot on experimental black-and-white Polaroid, like stills from a lost Dreyer movie. Meanwhile, the dilemma of having singles on the LP was circumvented by making those singles (also being re-released separately now) sound nothing like the album tracks: “Subculture” was radically re-sung and remixed into an amped-up Hamburg-harpsichord disco beast; while Low-life’s truncated “Perfect Kiss” edit played like a trailer that only hinted at the grandeur of the 12-inch single released the same week as the album.

To further the confusion, the “Perfect Kiss” video, recorded live in New Order’s practise room, featured yet another version again, although this hardly mattered as, at over 10-minutes, practically no TV station ever played it – another perfectly Factory promotional tool.

Directed by Jonathan Demme, fresh from Stop Making Sense, and exquisitely photographed by veteran cinematographer Henri Alekan, who shot La Belle et la Bête for Cocteau and chased Audrey Hepburn through Roman Holiday, that majestic monster of a promo takes pride of place among two DVDs of video extras in this set. The album, included on vinyl and CD, is further enhanced by an additional CD of early jams and rough mixes, showing tracks in early, mostly instrumental stages. Some differences are fascinating – “The Perfect Kiss” here is a softer thing, like Shannon dancing off with “Thieves Like Us.” Most surprising, though, and demonstrating how prolific they were, might be “Untitled 1,” a discarded writing session workout that sounds very like it is about to become “Bizarre Love Triangle,” key track to New Order’s next LP, 1986’s Brotherhood.

It is the three-and-a-half hours of mostly unreleased live footage, however, that is the real meat. All cowbell and overheating computer chips, these five 1985 shows, shot warts and all from Tokyo to Toronto, demonstrate how phenomenal New Order were in performance at this stage, even – especially – when things were almost falling apart. Eschewing backing tracks to play sequencers and samplers “live,” what becomes clear is just how incredibly hard all four members worked onstage to keep it all going, pushing themselves and their unreliable, tetchy technology – machines truly not designed for this kind of road wear – to the limit.

(The live highlights include: Tokyo, 1985: previously released as Pumped Full Of Drugs, this show from the band’s first tour of Japan finds them battling new gear and unanticipated cultural differences, as the audience claps politely after each song, then sits in complete silence until the next. But the mounting frustration feeds a demonic energy. Opener “Confusion” rarely sounded better. Manchester 1985: filmed as a live drop-in for the BBC’s weekly music magazine Whistle Test, this is only three tracks [and the last is partially reconstructed from unbroadcast footage], but it’s an invaluable snapshot of New Order playing at home in their club, the Haçienda, in its pre-acid days. The Velvetsy “As It Is When It Was” wouldn’t be released until the following year’s Brotherhood; “Sunrise” is near-violent. Toronto, 1985: this majestically rough-and-ready document, filmed with a single video camera from the side of the stage, is the most intimate show here, and showcases just how hard New Order work on stage. It’s also precious for preserving the most debatable pair of shorts Bernard Sumner ever sported.)

To stretch one of their favourite movies into a metaphor – Kubrick’s 2001, which was on heavy rotation on the VHS during the album’s recording – if the Power, Corruption And Lies epoch saw them discovering the big black monolith on the moon that was “Blue Monday”, the Low-life era is where they took that knowledge and blasted off for Jupiter and beyond, accompanied by technology that had its own personality and peculiar agenda. They all went spellbindingly mad on the way, and they gave birth to a starchild. There are imperfections everywhere, and it is perfect.

STEPHEN MORRIS AND PETER HOOK

ON THE MAKING OF LOW-LIFE

If I ask you about recording Low-life, what’s the first sense memory that comes back to you about being in the studio?

STEPHEN MORRIS: My memory of being in the studio is…being in the studio…waiting to go out. For Low-life, we wanted to go back to Britannia Row [where the previous album, Power, Corruption & Lies was recorded], but it was booked up for the time that we wanted. So we ended up going into the old Decca studio – Jam, it was called then, on Tollington Park Road, near Finsbury Park. Which was a nice little studio, it was really good.

PETER HOOK: Mike Johnson, the engineer, had done his homework in making sure Jam was very well equipped. We were living in London again, so it was a great escape to get down there. I think we were living in a house just next to Hyde Park that was next to Princess Margaret’s. It was really weirdly decorated, a bit run down and a bit shitty, but I suppose it suited us perfectly.

SM: The thing was, you see, we’d got used to going to London to do our recording, and there were a lot of…distractions in that town. And there still are. Yeah. We went out a lot. Which gave us a lot of inspiration. And also meant that we didn’t start – because you always start an album saying, “Oh, it’s great, we’re going to start at 9 o’clock in the morning, and we’ll finish at nine o’clock at night, and that means we can go out…” And then you’d go out at nine o’clock and not get back in until three in the morning, and so you didn’t start until one o’clock the next day, and pretty soon you’re going out without the window to do your work in. But we started off with the best of intentions.

PH: It was a pretty standard New Order affair – we were trying to get fit in the morning, I went running every morning, and the others would struggle to join up with me. Rob Gretton would collapse at the gates after he’d done about 20 yards, and Gillian would last for about another 20 yards longer before she dropped off. So I’d start off jogging round Hyde Park, I was full of energy in those days. And then we’d drive to the studio after myriad arguments along the lines of “Why aren’t you fuckers ready? Why did you say we’d leave at 10?” – and all that crap that was just the same as normal. And then we’d start work in Jam recording.

SM: I can remember being in the studio and doing a lot of work. Some of the songs were finished when went in, some were half-finished, and one of them, “This Time Of Night,” was just a vague idea. “The Perfect Kiss” was kind of one that was half-finished. So, I remember that. And I remember it was dark, because it was going into wintertime, at the end of the year.

PH: I must admit, it was quite a nice affair, from what I remember. We were just starting to go out in London with Kevin Millins, a friend of ours in London who used to run Heaven, so he knew all the places to go. We’d go to the Kit-Kat Club in Notting Hill, a punk club, and we were also going to Taboo in Leicester Square, so we were well entertained. But we weren’t too wild that we couldn’t work with it. Mike Johnston in particular kept us going. Mike was always the – everybody listened to him. I’d suppose you’d say it was probably a good balance, and it was actually, from what I can remember, actually quite a nice time doing Low-life. The confusion in my memory is that we did the start of [the next LP] Brotherhood in Jam, as well, when our relationship was starting to dwindle, shall we say.

I wanted to ask about influences – both musical and otherwise – on the album. Musically, it seems to me, this is the one where the Ennio Morricone influence kind of explodes. There’s “Elegia,” obviously, but I think you can hear a hint of Morricone in about half the tracks, including “The Perfect Kiss.”

SM: Oh yeah, we were pillaging Morricone.

PH: Yeah, but don’t forget that that fixation started with “Blue Monday.”

SM: “Sunrise,” has got a bit of Morricone, “Elegia,”obviously.

PH: “Elegia” is an interesting story. We were given free time at CTS in Wembley [a studio complex associated with film scores, including the Bond movies] , because the guy who used to cut our records said, “Oh, we’re opening a new studio in there, do you want to have a free day, you might decide you want to come back and book it, and that would make me look very good.” His name was Melvin, he was a real character. He used to smoke incessantly while he was cutting the records, and we’d be stood there going, “Does the ash not, y’know, get in the way of the cut, Melvin?” And he’d go: “Listen – fairy dust. No charge.” So, when we went to record “Elegia,” we were like, “Well, how much time have we got?” And he said, “Well just do a day, eight hours.” And we were going, “A day for us isn’t eight hours, we normally do 12, 16 hours in the studio.” And he said, “Well, that’s okay. It’s a 24-hour thing, the next session isn’t until 10 the next morning, so feel free.” So we went along and we felt very free. We were all off our heads on whizz, Barney was programming like a demon, and we ended up doing all the backing track for “Elegia.” I think we had started on the idea before we got there, but we elaborated it into the big long version, because we wanted to do an Ennio Morricone-style soundtrack. We didn’t really have time to edit while we were doing it, so, if you listen to the bass guitar on the long version, there are a lot of mistakes that couldn’t be re-done. But we just had a great time doing it. We’d record the drums and effects and stuff, then we’d break off while Barney programmed a bit more, then we’d record those parts, and then I’d put my six-string bass guitar on, and Bernard would put his guitar on, and we built it up like that. We ended up being in the studio all night. Melvin came to us, and said, “Are you going to be finishing soon? Only I’ve got to pick my two nephews up from school, I’m supposed to be taking them out.” And we said, “Well, bring them here.” So his two nephews turned up at the studio, they were called Justin and Ben, and we thought, for some insane idea, it would be great to put them on the track, just going, “My name’s Justin.” “My name’s Ben.” It was ridiculous. We didn’t use it [on the album version] in the end, but it kept Melvin happy. Then he took them home, and we were still there, and then we were still there at nine o’clock the next morning. Melvin was literally crying in the corner, because he had a client coming in at ten. But we’d done it. We’d done a 17-minute version of “Elegia,” and we were desperate to use it. If I’m being honest, I think there was a feeling that the 12-inches missed out on a lot of opportunities – for people to use them for stuff – because they were so long. And that’s why putting a shortened version of “Perfect Kiss” on the album to make it more commercial was tempting, and also to put “Elegia” on in a shortened version, so that people could use it, was tempting. We felt a temptation on these two tracks, we didn’t want to waste them. “Elegia” on the album was an edit – we didn’t even re-record it, which was quite unusual for us. I thought we’d take the opportunity to re-record it, but I think we must have ran out of time.

SM: Obviously we were listening to a lot of spaghetti western soundtracks. We had a cassette player in the car, and we had Ennio Morricone and the Clockwork Orange soundtrack on all the time. But we’d used up A Clockwork Orange when we were doing Power, Corruption & Lies, so this was more of your spaghetti western-y one. And western-y things in general. “Love Vigilantes,” was originally called “Western One,” or “Love Grows” or something. We thought, “Oh, wouldn’t it be great to do a country & western song?” And once we’d decided that, it was quite easy: do something a bit like “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town,” was the idea.

PH: It was a much friendlier, convivial atmosphere, and people used to bring their records down, and we’d play records in what was called the lounge, and shit like that. It was much more a family affair – before the family got to Christmas and started falling out. So things like listening to music together…and I suppose it was because we were young.

In terms of the other influences on the album, you’ve already mentioned that you were going out a lot at night during the recording. Aside from making it a bit more difficult to get up in the mornings, how did that impact on the making of Low-life? I was thinking that maybe [the fabled fetish club] Skin 2 comes up a bit in the memory.

SM: Well, it would do!

PH: I think, if you go through tracks like “This Time Of Night,” and “Sunrise,” and also “Subculture” they were very inspired by what we had seen in Skin 2, the leather and rubber club: that kind of darkness, that underground feel, that dirtiness. We tried to bring that out in the music. We wanted a louche feel, and we did very well in capturing that louche feel, not only of us, but also of London at that time. All those underground clubs, like Taboo, Skin 2, Kit-Kat club, were very important to the sound of the album. I do think Low-life catches the mood.

SM: Hmmmm – how did it impact? Well, yeah, it was the up all night thing. I think “Subculture” owes quite a bit of a debt to going to Skin 2. Like: “What the fuckin’ell’s this place?” We were quite lucky, because we had a friend, Kevin Millins, who did Heaven, and he could get us in to any club that we wanted. “Oh, he can get us in there, and in there…Oh, they’ve got a bit of a strict door policy – oh, never mind…” So, herm, yeah. I think that inspired “Subculture,” certainly lyrically. It was either that, or – well, see, we had to drive through Regents Park to get to the studio, but I don’t think it was the zoo that did it. Bernard was writing the lyrics in the studio, and I think that the Skin 2 experience was a lot to do with it.

PH: Those nights in Skin 2 were fucking wild. Absolutely wild. And, literally, we were just voyeurs watching the goings-on. But we did manage to capture that. We managed to capture the louche feeling of all of those underground clubs in London with “Subculture,” “This Time Of Night” and “Sunrise” there was a darkness that we were able to monopolise. It all added to the atmosphere, which was actually quite a nice, safe atmosphere, it has to be said – we didn’t count having your bottom smacked as violence then. It was a kind of noble thing to do. Especially if you were a politician.

I wanted to ask you about “The Perfect Kiss” in particular. I think you first played that live almost exactly one year before Low-life came out, when it still had its glorious original title.

SM: Yeah.

It’s a shame you had to change that.

PH: Well, we didn’t have to change it. The thing is, these things seem like a great idea at the time. But then, you don’t want the crowd shouting at you when you’re onstage, “I’ve Got A Cock Like The M1.”

SM: Yeah. It really wasn’t going to fly. Particularly when we were trying to get a deal with an American record label. I don’t think they would have went with that.

You could have changed it to Route 66.

SM: What, “I’ve Got A Cock Like Route 66”? Hmmm. Yeah, that would have gone down well. No, no. I quite like these box sets, because they all come with an age certification on it – this one’s got “15 Strong sexual references, language.” So it would probably bump it up to an 18 if we’d used the original title.

What were the roots of that track?

SM: “Perfect Kiss” was very influenced by – although it’s hard to believe – by Shannon’s “Let The Music Play.” We thought wouldn’t it be great to do something like that. And the only thing that stuck was the intro. We wrote the intro, and I think you can tell on one of the Writing Session tracks included on the box set, it’s got the same intro, but it goes somewhere completely different. So we managed to get a Shannon-kind-of intro, but then we had nowhere else to go with it. It was quite interesting listening to that completely different version of it.

The 12” version of “Perfect Kiss” is such an amazing thing. How long did it take you to make that recording?

SM: Not sure. Recording it…it was done in bits, really, because everything was done in bits. All the mixes were made of loads of edits, we didn’t do the entire song from beginning to end, it was lots of sections.

PH: From start to finish, “The Perfect Kiss” took nine months to programme and decide on the bits. Bernard, Steve and I were very good at using our respective strengths, and we got the tour de force of the start, and the end, and all the bits in-between before Barney did the vocal. So it had a great form, and, in those days, a mixture of Pernod and a great backing track would inspire Bernard quite well. And then we would listen to the tapes and go, “Oh, that’s not a bad bit, that line, and oh, that’s not a bad bit,” and then between a few live takes, you’d get the bones of it, and then you could build on that for a vocal. At this point the three of us, me, Barney and Steve, were working together on the vocal and the vocal melodies quite well. So it was very much a co-op effort. But, I mean, Barney, I must admit: as a keyboard writer, and a keyboard programmer, he is exceptional, he’s amazing. All the keyboard lines and all the synthesiser lines on the whole Low-life album are written by Barney. They may be played by Gillian on the LP, but Barney wrote the whole bleeding lot. I mean, the guy is an absolute genius when it comes to things like that. He’s got the vision to imagine – which I may have from a bass guitar point of view – but he had the vision to layer the synth lines the way he does on “Perfect Kiss.” I’m not blowing smoke here, I’m telling the truth – the guy is such a genius when it comes to creating soundscapes and writing keyboards, in particular. He used to spend hours on it. His guitar always came to him quite naturally, but he had to spend hours on the keyboards stuff, constructing these things.

SM: I know it took a bloody long time to mix “The Perfect Kiss.” It took a couple of days to mix it, because we did – how many versions did we do? – we did the 12” A-side, the B-side, and another one, “Perfect Pit” so we did three versions, and it took a least couple of days to mix it. The other thing about it that I can remember, is that we were trying to get this deal with Warner Brothers, because we hadn’t got a deal in America. And we thought it would be great to put Porky Pig at the end of “The Perfect Kiss”: y’know, the “Th-th-th-that’s All Folks!” And we thought, well it’s Warner Brothers, they’ll just let us have it for nothing. Yeah. No. “That’ll be one million dollars if you want to use that.” So we just sampled a pinball machine instead.

It probably strikes people odd these days, but I can remember THE OUTRAGE that you were actually including a single on an album

SM: Oh, I know

But how much of a discussion was that for you in the group? Did it feel strange, and was it something you were reluctant to do? Or am I making too much of it?

PH: No, you’re not making too much of it. I think, personally, we should have stuck to the principle of not having singles on the albums. When we were Joy Division, we spoke about the things that we hated, and one of the things that we all hated was that a band would release a single, and then put the single on the album, and you’d have the track twice. That used to really piss us off, and Ian Curtis in particular thought it was a dirty way of taking advantage of the fans. So the idea that we would not put our singles on our albums came from that, and it was just that punk ethic of wanting to be in charge of our own destiny, and not wanting to do what everyone else was doing because we didn’t agree with it, and the same attitude that we had to press and videos early on.

SM: Yeah, it was something we were reluctant to do. Because, ever since Joy Division, it had been: well, singles are singles, and an album is a collection that’s a completely different thing. It was going back to bands like The Kinks who used to do singles, just put a single out when you wanted. Which is a great way of working. It was difficult because we were doing the 12” idea, and doing a 12” single, it’s like, well, you can’t put that on an album, it’s too long. So the first bit of selling out was we’re going to do a 7” single, too. And then it was, well, the Americans want you to put the single on the album. So, there you go. It was our first bit of compromising.

But, of course, both the singles – The 12” “Perfect Kiss” and “Sub-Culture” – were radically different versions to the tracks that appeared on the album.

SM: Oh, yeah. That was the idea, I mean, if you’re going to do something, then do it differently. The fact that we then made a movie out of “The Perfect Kiss,” and it was a different version again. And then we stuck to the “No. We’re going to play live on our own bloody video…” Yeah, we did make life difficult for ourselves. Which is I think why a lot of people liked us. And so I could understand that whole attitude of: “Pah, selling out, putting a single on the record…”

How do you remember the “Perfect Kiss” video shoot? Was it a lot of pressure to try and get the track recorded live in one take?

SM: Yes, well, first of all, we’d written “The Perfect Kiss” on a load of old…it was kind of like, it was pre-MIDI gear. But then we got all this wonderful, fantastic new Yamaha MIDI stuff, literally just a couple of weeks after we’d finished recording Low-life. And so then, we had to reprogramme the whole thing again on this load of new gear, which we still didn’t really know how it worked, totally different stuff. And I think it was the first thing we did, we had to make this film using this new stuff.

PH: We were desperate to get the track recorded in one take, which we did. But there was a lot of editing in the actual filming. Don’t tell anyone, but we sometimes pretended for the filming, so that they could get the bits they wanted.

How did Jonathan Demme become involved?

SM: It was [Factory Records’ video guru] Michael Shamberg’s idea, really, to do it with Jonathan Demme, and he got Henri Alekan, Cocteau’s lighting cameraman to shoot it – and so then we’re going to do it in a shithole, which was our rehearsal room up on Cheetham Hill, which wasn’t exactly renowned for its atmosphere. Yeah, we did make life hard for ourselves.

PH: Yeah, Michael in America got Jonathan Demme involved, and Jonathan was a fan anyway, and a Joy Division fan. So, in typical fucking Factory fashion, you fly this great director over from America – and, don’t forget, at this point, the Hacienda was losing £10,000 a week – and he hires a top-notch film crew that must have cost a fucking fortune, and then we disassembled our practise place in Cheetham Hill. We took all the skylights out of it, it was a former Gas showroom, where they used to fix gas cookers, it had nine skylights in it, and Jonathan wanted all the skylights out so he could film from above. Which mostly didn’t get used. And then the whole thing was lit up like a Hollywood movie set, which drew every scumbag in Salford to it like it was the fucking Star Of Bethlehem, and we got robbed for months after that. In the end, we had to concrete over the skylights because of “The Perfect Kiss” video, so we never saw any daylight in there again. So, thanks Jonathan, for that. But Jonathan Demme was a great guy, he was very funny and he really just wanted to capture the band just playing the track.

SM: The filming of it felt very awkward – because someone points a camera at you and shouts “Action!” and then you…don’t do anything at all, except press a button, and sort of stand there wondering what the hell are you supposed to do. But apart from that, everyone did a great job. I think the actual filming only took a few days. It was a great experience, Jonathan Demme was a lovely man, really nice. The track he really wanted to do was “Love Vigilantes,” he had an idea for making a video for that, but we never did that one. The great thing was, after we’d done the filming, we went to view it, and we had to go to a cinema in Manchester that’s not there anymore. And to see yourself on a 15-foot high screen, that was a bit weird.

PH: I remember, it was really weird, because I look at myself and I look such a bag of shit in it. Because we just weren’t bothered about anything. About the only person who dressed up a bit for the video was Gillian. We were just like: Yeah, whatevever. The most important thing was writing and playing, without a shadow of a doubt. Everything else, like the videos and interviews, were just irksome.

SM: But doing that film was good, and we were doing something different. Much like we’d tried to do with “Elegia,” which was originally a soundtrack for a film that never got made, 17 minutes or so, and then we just stuck it down on the album. But, yeah, we were quite into films. And the filming of the “Perfect Kiss” video was the easy bit, actually. It was afterwards, when you’d done this live take, then trying to make it sound a little bit like the record – that took bloody ages, mixing it and re-mixing it and mixing it again.

PH: The big problem is that when they finally put the live backing track onto the film, instead of putting a Left Channel and Right Channel on it, they somehow put Left and Left on it. So, it phased, and it sounded really weak and watery, and we never noticed. It’s typical – we did the “Love Will Tear Us Apart” video live, and then the Australians replaced the live take with the record, and now everybody plays it with just the Australian record on it. So the “Perfect Kiss” video had two left channels, so it was cutting out, and you’re also missing a lot of the parts, where the parts were supposed to be in stereo, they were missing, but you didn’t notice because it was phasing, so it just sounded like a weird mono. The way we finally found out is, we were sat in a hotel in Austin, on tour, and “The Perfect Kiss” came on this massive TV screen that they had on in the bar, and we were sitting listening to it, going, “That sounds weird…why does that sound weird?” We’d never really listened to it properly before, and so we did some investigation, and found out that in the cutting room, when they put the audio on the video, they’d used two lefts. And it sounded shit, basically. So, after that, it was corrected, and the left and right appears on the later ones. So, it was very typical. We were doing everything in our power to destroy our own career. Time and time again. Just like insisting on doing “Blue Monday” live on Top Of The Pops, rather than miming. They were great days, because we were so awkward, and so ornery. And, of course, Rob Gretton and Tony Wilson were always big fans of everything we did that was different, and they came up with a lot of their own ideas about how we could be different. And we were like, “Oh yeah, that’ll annoy em, that’ll be good…” The great thing about “Blue Monday” on Top Of The Pops that everybody loves is that we fucking played it! And other people didn’t do that. It really made you special. I hate to think what kind of group we would have turned into if we’d started miming. Ironically, the first time we did mime was at the San Remo music festival, in 1988, we mimed to “True Faith” and it had an audience of something like 32 million. So, if New Order were going to expose themselves as mimers, there you go – we did it in front of everybody, we did it to the biggest music audience in the world at that time. We were always fucking stupid, it was brilliant.

Not only did Low-life break the principle of not including singles on the album, it also saw you doing something else you’d never done before, and never did again – using photographs of the band on the cover. How was that done? Was it a hard decision, was it sprung on you, or did you have a discussion?

SM: It was kind of sprung on us.

PH: Yeah, like the singles thing, with Low-life we got stitched up twice. Peter Saville, Tony and Rob worked out that if we got our pictures taken, they might get our pictures on the sleeve, which everybody was moaning about us not doing – particularly the Americans. They felt that “Hey, man – the personality’s not coming through.” And we’d be saying, “We don’t want our fucking personalities to come through. Have you met us? We want people to think we’re intelligent and we’re actually doing something here that’s revolutionary and artistic, not a bunch of pissed-up bastards.” On that level, the mystery always helped.

SM: Saville’s concept was that he wanted to “de-mystify” the band. “We’re going to do de-mystify the band, and we’re going to do pictures…” So we were like, Okay, you’ve got an idea, that’s a start.

PH: I think Pete thought it would be a good idea to put our picture on the sleeve, for many reaons – but then he felt that he had to please us, by hiding our pictures under the tracing paper. That was a great gimmick of Saville’s to put our pictures on and then obscure it. The fact that they sort of tricked us into doing it was a little irksome, though.

SM: To do the pictures, Saville knew us quite well, and he realised that if all four of us were in the same room, he wouldn’t get a photograph of any of us, because we’d all be taking the piss out of each other. So we had to go one at a time to Saville’s studio in Ladbroke Grove and be photographed.

PH: We only found out they wanted to use the pictures for the cover at the end. We were told it was a press shoot. And, yeah, we went down and did the pictures individually. Because, when we were all together, it was really…unserious. Nobody would concentrate and we were always fucking around. Most of the time, while Pete was trying to tame us, we’d be moving all his shit around, because he had OCD and he knew where everything was, and everything had to be straight lines, and we’d go around moving everything, just to annoy him. So to take it seriously, the only way they could do it was to bring us down separately. So that’s how he got a sort of serious photo.

SM: He shot us with this Polaroid. It was a great thing, actually, it never really caught on, though: black-and-white Polaroid slide film, you took the picture, put it in a little machine, and it developed like a Polaroid, but it had a very peculiar quality to it.

PH: Then he stretched the image, to change our appearance. But it was okay -the thing is, by that time, we were so busy – we toured after we recorded the LP, we went all over the world, we did a three-month tour of the Far East, we were really, really busy, so, to be honest, even though they kind if jumped it on us with the sleeve, we kind of thought, oh fuck off, let’s get on with it, it’s not the end of the world. We just carried on and thought, ‘Right, let’s make sure we don’t fall for that again on the next one.’

SM: And for some reason – no money changed hands – but Peter was particularly taken with the picture of me. I didn’t think it was going to end up on the front, but that’s what happened – me and Gillian are on the record sleeve, and Hooky and Bernard are on the inside. Then when the CD came out, there was a bit of democracy restored, you could have it so you could have whoever you want on the front. Which meant that, for a while, I’d go to HMV and find that they’d put Bernard on the front, so I had to go in and change them all while no one was looking.

The live videos are such a big component of the box. I was watching Pumped Full Of Drugs, the Tokyo concert, which I hadn’t seen in a long while, and I thought it sounded fantastic – much better than I remembered, if you don’t take that the wrong way. But the reaction from the crowd is a little…muted. Do you have memories of that particular audience?

SM: Yes. The show that was filmed was the second night in Tokyo, and we’d never played there before. And there were a few things we didn’t realise.

PH: One thing we didn’t realise was that the Japanese don’t like to say the word “no.” They try to avoid saying it, and so they might say something like, “maybe.” And we were asking the production team for ridiculous things: “Do you think you could get Bernard a 1964 Vox combo, like the Beatles used to use, because we had ours stolen?” And the guy would go, “…maybe.” And I’m like, “Oh? Really? Well, do you think you could get me a Vox 2×15 cab?” And he goes, “Oh…maybe.” And we were like, “Fucking hell, this is great.” And so we were asking for more and more old, vintage equipment that we’d lost through the years, and the guy kept saying maybe. And as we were getting nearer and nearer to the gig, shall we say that tempers were getting frayed, because every time he said “maybe” what he actually meant was, “No, mate. You’ve not got a fucking chance.” So everything was getting really, really irate between us and the Japanese production team, just because of this cultural difference.

SM: When we played the first night – the one that wasn’t filmed – we were rather taken aback that all you got from the crowd was sort of like polite applause. Nobody stood up or anything, they all just sat in their seats and clapped quietly.

PH: The atmosphere was very dead and very boring, we were like, “Oh my god, this is shit, we’ve come all the way to Japan to play and the audiences are like this…” It was shocking, really, in a way.

SM: So we came of, and we were like, “Yeah, that was hard work.” We came off and the promoter asked if we were doing an encore, and we were like, “We’re not doing an encore after that.”

PH: I said, “Mate, we’re not doing an encore for them, they’re arseholes, they never got up, they never danced, they never did anything, we’re not doing an encore.” But then we were backstage, talking, “Oh they were a bunch of bastards weren’t they?” And Barney said, “Yeah, it was shit, awful atmosphere.” And I said, “Why don’t we go on and do “Sister Ray,” fuck ‘’em right off, do a really shit version of “Sister Ray”?” And he went: “Okay!”

SM: In the meantime, though, they had started to let everybody out. And then we decided, no, let’s go on again after all, and a do a 15-minute version of “Sister Ray,” jut to piss them off, which is what we did quite a lot. And, of course, when we went and did that, it turned into a riot.

PH: As soon as we started playing, all the people who had been going out started trying to get back in. They all rushed the stage. There was a massive riot – but none of it’s reflected in the video, because they didn’t film it.

SM: But what we didn’t realise was that somebody had died at a Who concert. And so there was like strict crowd control at gigs in Japan after that. The crowd literally couldn’t actually stand up. They were sort of penned in.

PH: Because of that Who concert, they’d installed metal barriers between each two seats, so two seats were together and then a metal barrier would come up, and at the end of every aisle, because it was a seated venue, there was a security a man, a security man on one end and a security man on the other end, and they wouldn’t let them stand up.

SM: And, so yeah: the audience went mad and invaded the stage, and the police were called, and we got a telling-off from the promoter, that we weren’t to do that ever again. So…the second night was slightly tamer, as is reflected in the video. If we’d filmed the first night, it would have been a lot more interesting. But no. Or if they’d filmed both nights, it would’ve been even better. But no.

PH: It was just a really weird day that we filmed, and everybody was just a bit fucked off, and it was one of those things, it was probably jet lag, looking back. We weren’t very professional in that way. And this is a thing I used to love about New Order: if we were fucked off on stage, and something was going wrong, Barney wouldn’t pretend. He’d just sit down going, “Fucking bastards.” I thought it actually showed a lot of emotion and showed that we were actually human. There was none of that the show must go on bollocks with Barney, I’ll give him that.

SM: Another thing that we realised was that everything we did in Japan was strictly regimented. Basically, we’d gone there, we were going to record two tracks, we were going to shoot the concert video, we were going to edit the video, we were going to mix the sound for the video – and according to the schedule, there was about three or four hours sleep a night, so it was like really, really intensive. When I was looking at Pumped Full Of Drugs for the box set, I thought, like you said: yeah, it’s better than I remember. Because I think we all thought…aw. And we were ill, as well, for that gig we had all managed to catch a cold in China, we’d played Hong Kong on the way, we were all ill. So it was better than I remembered it. The other thing, when we were doing the video for the box was, if you look at the setlist from the night, you think – where are the other tracks? Surely we must have filmed them? And I think when we were editing the video back then, we sort of decided, “Well, it’s only going to be so long, so which ones do we get rid of?” So we literally just crossed them off and I think the video tape we edited out ended up in the bin. All the songs were filmed…but timing constraints – let’s say timing constraints – meant that we never got round to editing them or fixing the sound for them, because it all had to be done by the time we went home, according to this schedule we were on. But it’s a mystery. I was going through piles and piles of tapes with Japanese writing on them, thinking that one of them would surely have all the tracks from that gig on it, but none of them ever did.

Watching all those live videos, you can see how hard all four of you were working on stage. When you look back at the technology you were using then, are you surprised that it didn’t fail more often?

PH: Well, yeah. We used to spend all day, literally from 11 o’clock in the morning, fixing everything. Barney, Steve, Gillian, me, we’d all be there, with the roadies, literally trying to hammer it all together. And it was a fucking nightmare. I’d be driving round, taking synths all over each city we were in to be fixed, desperately trying to get them back for the gig. We had five Prophet-5s, we had four sequencers – we would have had ten of each if we could have carried them. The amount of money we had invested in the technology was unbelievable. Five Prophet-5s were £10,000, which now would be like £200,000 worth of synths. And none of them worked. You’d literally be banging them, not in frustration. We had a gig in Germany, and we couldn’t get the Emulator going. The lights were flashing, and someone said, “Oh, it looks like it might be something to do with the power supply.” So, we took to banging it on the leg, and, if you hit it with the hammer, just with the right amount of force – not too much – it would work, and you’d get through the gig. I remember, there was a phone call at some gig we were doing in Germany, and it was someone from Blancmange, asking which foot of the Emulator you hit with a hammer to get it to work, because they were suffering in the same way we were. So, that technology, God almighty, Godstrength to us all for doing it. But Rob Gretton was a great believer, as we all were, in playing it all live. I’d been to see Depeche Mode, and they were using a 16-track, with all the Emulators and synths on and all that, and the 16-track was really reliable, and they had a spare 16-track, but we wouldn’t do it, because we were punks. In our eyes, it was ripping off the audience, we just didn’t believe in backing tracks or anything like that. The interesting thing, though, was that every night, because the gear was all analogue, every night was different, and every gig was different. Some of them were absolutely catastrophic. And some of them were terrible. And some of them were fucking amazing. And, in a funny way, that appealed to us at that age – whereas now, it fills me with dread. So, yeah, it was a very difficult time, making it all work.

SM: A lot of the stuff we took on tour just after Low-life was all new gear, though. And the reason it was all new gear was because the stuff that we did Power, Corruption & Lies – and, actually recorded Low-life with – was very, very unreliable. So when we got the new stuff, we were thinking, “Oh it’s great this, it doesn’t go wrong nearly half as much.” When we did the gigs after Low-life, it didn’t go wrong very often at all. But it did sometimes, and it was still difficult, because it really wasn’t what the stuff was designed to do. You were supposed to just keep it in a studio, not take it out on the road and do gigs with it.

PH: We were very experimental in what we were doing. But, yeah, the amount of work we had to put in, all of us, Barney, Steve, Gillian and me, was fucking incredible. A lot of the time, the only people who knew how the gear worked was us. Because the roadies weren’t there when we were wiring it together, so. And it was so complicated, and it was so delicate. We should have billed Sequential Circuits, the folk that made the Prophet-5, because literally, we would be phoning them up all the time and giving them a running report on what was going wrong with the synthesisers, hoping that they could magically make it work over the phone – this was before email, of course – and they would then incorporate all our problem-finding into the next sequencer, or the next synthesiser. We were doing their research work for them while we were on the road, same with Emulator, same with the Voyetra synths.

SM: Yeah, we did all work hard…I couldn’t do that nowadays. What were we thinking? But we had this thing where, up to a point, you would write songs live on stage. Like you said, when we played the first version of “The Perfect Kiss,” it wasn’t finished, but you’d just get an idea: “Oh, that’s a good idea, let’s play it next week.” You know: we don’t have any words, but you just make some words up. Yeah, we did that a lot. It was just how we did things.

When you’re digging through old tapes, putting this stuff together for the box sets, are you ever surprised at what you find?

SM: Yeah, it was very surprising. At the time, back then, you’d listen to something and think, “Aw, that’s rubbish…” We would jam for ages, just round a sequencer thing, then sit back and listen: “Is anything any good?” Then: “Nah…let’s do something else and do another one.” And so, in our quest for perfection, we probably let a few things go.

PH: We were rehearsing, if I remember rightly, five days a week in our rehearsal room in Salford, in Cheetham Hill. We would have three, four, five songs on the go all the time, and refer back to them. We weren’t off our heads all the time – like we were from 1987 onwards. We actually got a lot done. For this Low-life box set, one of the interesting things is there are a couple of new tracks, jams, ideas, that sound really good. And you’re like – wow, did we abandon that one? That’s weird. Just a couple of ideas-tracks that never got used, and they’re there in the box set. There’s also some odd mixes and stuff. Because, by this time, because we had some money behind us, we were able to experiment a lot more with tape – we were able to buy more tape, and record more versions. It’s weird, when you look back at Movement and Power, Corruption & Lies, there are hardly any alternates – we would only record the final mix, we wouldn’t record any of the in-between mixes, because we couldn’t afford the tape, because it was so expensive. So there’s the difference, we were starting to get a little more affluent, and were able to record a few mixes.

Where do you rank Low-life, both in terms of the experience of making it, and as an album among the other records you’ve made?

SM: I think Low-life was us sort of…it was really a peak of sorts, because we’d got the hang of stuff: we’d got the hang of technology, we’d got the hang of writing stuff and doing gigs, we were kind of like we’d become a semi-pro band. We sort of knew what we were doing on Low-life.

PH: It was our third album in four years. Fucking hell. We were a hell of a lot more prolific, as a writing team, in those days. We just got on with it. In my opinion, the whole wonderful aspect of recording, being away, doing something new, really ended with Low-life. It was great doing that album – but afterwards, once we got to Brotherhood, Barney and I were arguing like fuck about whether we were going to be an acoustic or rock-tinged group, whereas he wanted us to be a synth band. So the arguments and the divisions started there, which is why Brotherhood has two distinct sides. And, ironically, now, I’ve mellowed enough to enjoy the synth side more than I do the rock side. Don’t tell him that though. But Low-life was a hugely enjoyable experience. If I remember rightly, it was just before the tax investigation and all the bad feeling came into New Order about the Hacienda – the tax investigation was in 1985, and culminated in us having a hell lot of problems in ’85 and ’86. So this was kind of a golden period, we were all getting on quite well, and it was really enjoyable, we did feel as though we were all in it together. And I suppose we got three albums out of that rosy period, and I do think that Brotherhood is a really good album, too. Barney and I never got back that rosy feeling of working together until we got to Get Ready. But then, by the time we got to Waiting For The Siren’s Call, it had gone back. It was like going back with an ex – as soon as you’re back with them, you have a good time for a couple of weeks, and then you think, “Aw, fucking hell, I remember now…” So Brotherhood was difficult, Technique was difficult, Republic was the most difficult of all. But on Get Ready, Barney and I really found ourselves. By Waiting For The Siren’s Call, Gillian had left, and it was back to me and Barney fighting all the time. So, yeah. Low-life ranks highly in my memories of my young life. I remember that period, knocking round with Rusty Egan in the Embassy Club, and Rusty taking us down to Taboo to meet Leigh Bowery and all those people, we counted them as friends. We were knocking round with Siouxsie and the Banshees, Marc Almond, all those goths, we all used to go round together. And nobody was completely off their heads – there was no coke, so nobody turned into a twat. We were all just a few drinks in. One of my abiding memories is of going round the roundabout at Trafalgar Square. We were with Marilyn, Marc Almond and some of the Banshees, and Marilyn got out in the middle of Trafalgar Square with just a fur coat and a pair of Speedos on, and he stopped the traffic. And me and Barney were in the other taxi, going, “Fucking ‘ell, man. He’s got balls, in’ee?” There really was just a great, great social aspect to the recording of that LP, we really did discover London, and London did certainly affect that record as much as Manchester did. So yeah, they were good times. We had a really good year that year, travelled the world, had a great time, we were really breaking new ground as a group. Yeah, it was a wonderful time.

SM: Another thing about that period is that we were becoming producers as well, all of us. After Low-life, we ended up producing a lot stuff for other Factory bands, we were getting the hang of working in the studio with other people, how you recorded things, mixing stuff, editing particularly. And, also, I’d bought one of the first little digital recorders, and it could mix it down onto digital tape – which ended up being a disaster, because all the CD versions originally sounded shit, and it turned out it was because there was this little emphasis button that put loads of top on and took all the bottom off, and for some reason, it got left on, but everyone thought it was off, so the first CDs of Low-life really sounded bloody awful, and it took a few years before we realised what we’d done. Pressed the wrong button.

Well, it happens to the best of us.

SM: It does, yeah. I still do it today.

HOME