It’s early evening, just another day in the eternal boredom of British summer. In the front room of their terraced house, a schoolgirl does her homework whilst her mother knits and her father sits smoking his pipe. A television flickers quietly. Almost time for dinner.

Suddenly, a weird, piercing, pulsing noise begins. Dad lurches to his feet, face contorted, and grabs up a heavy metal ashtray. Then, swinging it like an axe, he starts smashing the TV to pieces, grunting, pipe still clenched rigidly between his teeth.

The girl and her mother look on. Their limbs spasm. Their faces shudder as though their heads might explode. The migraine noise screams on around them. Now, they are all on their knees, in the kitchen, lost in an animalistic family fit, tearing apart the cooker, the Hoover, the fridge. Outside, it continues, the street filled with their maddened, rioting neighbours, throwing TVs from windows, burning cars. Destroying everything.

Everyday folks in a sudden unexplained orgy of violence against domestic appliances. Some smoking pipes. It’s a Ballardian scene that would not be out of place in some early-David Cronenberg sci-horror. But we’re far from the realm of late-night cult movies here. In fact, we’re in our living room, and it’s teatime.

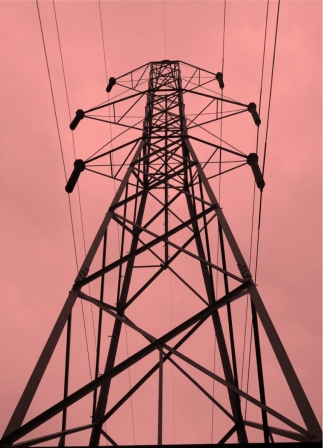

The sequence is the mind-meltingly unsettling opening to The Changes, a BBC children’s drama that went out on Mondays at 5.20pm in early 1975. It tends to be the only part of the 10-part series that people remember, if they remember it at all. But what follows is equally strange, as, following the cataclysm of “The Noise,” our schoolgirl heroine Nicky Gore (the pale, pensive Victoria Williams) is left alone in a silent Britain that has strangely rejected electricity and modernity – pylons and their “bad wires” become sinister markers in the landscape – and returned to the fields for a new dark age, superstition, witch hunts and all. At one point, Nicky is sentenced to be stoned to death.

Cannily adapted from a trilogy of novels by Peter Dickinson, The Changes bears some striking similarities with Daleks-creator Terry Nation’s adult drama Survivors, another bleak BBC series of 1975. Both present a Britain where the cities have been abandoned and feudal fascist groups enthusiastically spring up among the hedgerows, as though the seeds were always there, waiting. But The Changes ultimately gives a magickal, Arthurian twist to the post-apocalyptic futureshock. After nine episodes more or less realistically exploring what life in a fallen agrarian Britain run by self-appointed fanatics might be like, the final explanation for everything that has been going on is truly mad, rooted deep in gnarly national mythology.

In this, the series is emblematic of that feverish strain of weirded-out British children’s TV that blossomed like a fungus patch across the late-1960s and 1970s, then withered away in the early-1980s, never to be seen again. The likes of Children Of The Stones, The Owl Service and semi-Satanic/ Nigel Kneale-influenced Doctor Who stories such as “The Daemons.”

Dabbling in the occult, green pagan vibes and trippy psyche sci-fi, these were the kids’ TV counterpart to the British folk-horror cinema cycle that briefly flourished in the same period in films like The Wicker Man, Blood On Satan’s Claw and Kneale’s The Witches. All seemed to come bubbling up out of the landscape and divine currents then mingling in the air: the back to nature movement, in both its idealism and its bullying militancy; the attractions and dangers of denying progress; primetime ITV scare documentaries about suburban devil cults. Back then, when kids were much more likely to be out playing by themselves, it was easy to turn the corner of some derelict lane and find yourself in the cover of a Dennis Wheatley novel.

Adapted by writer-producer Anna Home, the woman who brought everything from Jackanory through Grange Hill to Teletubbies into our lives, The Changes doesn’t have Children Of The Stones’s mad, psychedelic narrative ambition, nor its present-day hauntological cult following. But, arriving on the heels of the candlelit nights and Government-imposed powercuts of 1974’s Three-Day-Week, it was more urgent about reflecting contemporary social concerns.

Home excises some of Dickinson’s weirder touches – notably a morphine-addict wizard – but melds and marshals the scattered events of his trilogy into a compelling parable positively crawling with the anxieties of its age. Alongside societal breakdown and ecological fears come religious fundamentalism, sexism and racism; broadcast when National Front marches were making the headlines, the only reasonable people Nicky meets are a band of Sikhs, dubbed “the devil’s children” by the superstitious white folks. Home’s ending, too, seems wilfully ambiguous: when, finally, the machines start running again and the roads fill up with traffic belching pollution, it’s hard to tell whether this is really supposed to be a happy outcome.

The Changes and its peers all attempted something quite unimaginable in children’s TV today: they actually tried to disturb children, in order to make them think. These days, kid’s TV drama seems preoccupied more with encouraging children to consume. That’s the truly disturbing thing.

A version of this review ran in Uncut magazine, October 2014